The following was presented to the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development on Thursday March 7, 2013 by the Executive Director of the Ontario Disability Employment Network, Joe Dale.

(Click here to download a PDF version)

Good morning.

First and foremost, I’d like to thank you for the opportunity to appear before the Standing Committee today. My name is Joe Dale. I have worked in the disability field for over 35 years, spending much of that time working in, training and consulting on issues related to employment opportunities for people who have a disability. Currently, I am the Executive Director of the Ontario Disability Employment Network, a professional network of employment service agencies from across Ontario, and I am the founder of the Rotary at Work initiative in Ontario which has been a catalyst for a number of employer engagement initiatives and strategies.

I have three key issues I’d like to speak to this morning. They are: ensuring effective services and supports for people who have a disability; employer engagement and support; and, youth employment for kids with disabilities.

Providing Effective Services and Supports

People who have a disability can work and have the capacity to make a significant contribution to the workforce. This is a fundamental fact that we must understand and accept. Another fact is that we, in the non-disabled community – in both government and in the disability profession – have only just begun to scratch the surface in our understanding of how to recognize this capacity and how best to exploit it.

There is no tool or instrument, that we have today that can effectively measure or assess capacity or help us determine the ‘employability’ of people who have a disability. Whenever we set out to measure employability or capacity to work, we invariably set the bar too high and discriminate against those who we deem to be too severely disabled to work.

This was made imminently clear to me recently when I was fortunate enough to travel to Connecticut and visit a Walgreens Distribution Centre where 47% of the employees have a disability. I’m sure you’re all familiar with the Walgreens story.

What was of particular interest to me was a statement made by Executive Vice President, Randy Lewis. Mr. Lewis recounted their early hires when they embarked on this journey of hiring people with disabilities. He talked about a young man with severe autism and significant behavioral problems who was to be their first hire. Mr. Lewis was asked the question: “Mr. Lewis, it seems that you deliberately started out by hiring someone with very significant challenges. Was that intentional?” Mr. Lewis responded: “Yes, we did, because we thought if we could get that first, difficult one right, the rest would be easy. What we learned though, is that we didn’t go low enough because the capacity of people was far greater than anything we had ever imagined.” A very profound statement!

Indeed, perhaps the most effective measure of employability is more properly gauged by each individual’s motivation to work.

Having said that, it is important that the services and supports each person needs is available and available in a way that makes sense.

We need to consider ease of access to employment services and supports. That it makes sense to the individual job seeker and that when they show up at the door looking for help, they can get that help as soon as possible and in a seamless way. Nothing takes the motivation out of someone faster than being bounced around from service to service, process to process, assessment to assessment and so on.

If the job seeker comes looking for help and they are sent to one door for an assessment or an eligibility determination, a different door to get an employment plan, another to get the case manager they didn’t even know they needed and so forth, not only have we lengthened the process out and made it extremely costly to deliver, but that person is at very high risk of losing their initial motivation and much less likely to follow through to the end goal of getting a job. Even those who endure it all, often end up back at the original door they first went to with the agency that offers the employment support services of job preparation and job development.

Services should be available using a wrap-around process. There is little, if any value in having silos of service with multiple agencies each providing a different part of the service. Employment agencies should be entrusted with providing as much of the supports as are needed to assist people to meet their career and job goals. If through the career exploration process, it is determined that a competency-based assessment or specialized training is required, the employment agency should broker or case manage these services on behalf of the job seeker to ensure continuity.

Job seekers with disabilities need access to the full spectrum of services and supports – pre and post-employment.

Those with limited education, training and work experience often need pre-employment supports. This includes employment-related life-skills, an understanding of workplace culture and responsibilities, resume preparation and interview skills training and so on. This should be based on time-limited, curriculum-based programs or training modules. These programs also serve to help the employment agency assess motivation; help determine the skills, abilities and aspirations of the job seeker; and, give a solid understanding of the supports needed to ensure a successful job match.

Supports don’t stop at the point of job placement. Employers also need support and it is the post-placement support that has the greatest impact on job retention and career growth. Employers need to see the employment agency as a specialist or as a disability consultant. As one employer once told me; “I’m an expert at making coffee, not at understanding disability”. Workplaces evolve and jobs change. Often retraining and even revisiting and revising accommodations are necessary.

Preventative maintenance, in the form of customer service with the business owner or manager can often prevent terminations, nipping problems in the bud before they become too much for the business to contend with.

The Ontario Disability Employment Network recommends that the HRSDC Opportunities Fund ensures that the full range of employment supports be available to people who have a disability, including both pre and post-placement services. Secondly, we recommend that services not be carved off into silos with different services provided by different agencies, particularly case management and assessment.

Employer Engagement

Through the Rotary at Work initiative we have learned two very important lessons:

First, that we must make a solid business case for hiring people who have a disability. We can no longer soft sell on the basis that ‘It’s the right thing to do’ or by appealing to charitable and feel good notions.

And secondly, that the peer-to-peer method of delivering the message works best. People respect and listen to their peers. In the broadest sense, this is evident when we use the business-to-business approach. Business operators speaking to other business operators, in the same language and understanding each other’s motivation of profitability gets traction.

On another level, however, the peer-to-peer method can be used within employment sectors as evidenced by the Mayor’s Challenge, where we have the Mayor of Sarnia challenging his colleagues and peers in other municipalities to hire people with disabilities within the municipal workforce; or the Police Chief’s Challenge, where London’s police chief, Brad Duncan has put out the challenge to other police chiefs across the province. These challenges are followed up with in-person contact and support from the Champion.

This peer-to-peer approach is also transferable on a more micro level. Using the peer-to-peer approach, we are now working with some major Canadian Corporations to develop strategies within their own ranks. Deliberate strategies that have department managers talking to their counterparts and peers in other divisions, departments and branches not only about why they should include people who have disabilities in their divisions, but also about how to successfully on-board new hires.

There is still a lot of work to be done to engage employers in many segments of business and industry but we are now seeing the tide turning on this issue. For many businesses, the question is changing from why hire to how do I hire.

In this regard we would recommend establishing a business-driven association of experienced employers, along the lines of the UK Forum on Abilities. Such an entity could carry on the important educational work that has begun while adding to its capacity, peer support, advice and consultation services to assist those who are having difficulty with implementing pro-active recruitment strategies and on-boarding new employees from the disability sector.

Wage subsidies, as a strategy to gain employment opportunities for people with disabilities is hotly contested across the country. The Ontario Disability Employment Network, and its members, does not support wage subsidies as an employment strategy. We have seen far too many abuses, where there was no intention to retain an employee beyond the term of the subsidy. Wage subsidies also undermine the ‘value proposition’ of hiring from the disability sector and set people up to be seen and often treated differently from their co-workers.

Employers, who understand the value that people with disabilities bring to the workplace, rarely, if ever, access wage subsidies. Smart employers tell us that, when they pay wages, they are, in fact, investing in that employee and through this investment, are more vested in achieving a successful outcome. When it’s free or subsidized the relationship is not the same.

If we are doing a good job at making the business case for hiring people who have a disability, wage subsidies should not be required. We believe these precious resources could be better utilized in other areas with greater impact.

Rather than wage subsidies, consideration should be given to accommodate businesses for any ‘real’ out of pocket costs that may be incurred by hiring someone with a disability. Consider financial support for accommodations, whether they be physical accommodations, technical accommodations, personal supports and job coaches, skills training and so on.

Perhaps consideration can be given to provide a subsidy where an individual, due to their disability, may take longer to learn the job than would be expected. But, a blanket approach where employers are paid to hire people who have a disability, without any long-term commitment is bound to end up with abuses and less than desirable outcomes.

Student Employment

Much greater emphasis and resources must be invested in kids who have disabilities. Students with disabilities are also shut out of the labour market. They graduate from high school, colleges and universities without any work experience on their resume. We must get kids engaged, at 15 and 16 years of age, in summer jobs and part-time after school jobs so they can gain the experience they need to learn workplace culture and life skills, and to establish career goals and paths.

A 2012 US study found that the number one indicator of successful labour market attachment for people with severe disabilities, upon graduation from school was having had a paid job while in school.*1 Through the Rotary at Work initiative, we have experienced this first hand. In 2010 we were approached by a young man,

Adam, seeking help to find a job. Adam had been called to the Ontario Bar in 2004 but due to his disability, had never worked. Not just in his chosen profession, never worked in any job and he was willing to do anything including serving coffee if that’s what it took. We were fortunate in connecting Adam with Deloitte, where he was eventually hired to work in one of their legal departments. Adam’s manager, however, clearly stated that they went out on a limb for Adam. That he was sorely lacking in the ‘soft’ skills and had a poor understanding of workplace culture. Fortunately Adam was a quick study and has maintained his position with Deloitte.

We have seen this example over and over again – accountants, computer programmers and many other qualified professionals as well as those simply looking for entry-level positions. In the HRSDC report, Rethinking Disability in the Private Sector, there is a notation about the significant increases in the proportion of adults with disabilities that have post-secondary degrees. If we can’t do better than a 51% labour market attachment for these individuals once they graduate, we have wasted, and are continuing to waste a lot of resources and talent.

We must engage kids with disabilities in the labour market, just as we do with kids who are not disabled.

We have an excellent example of where this is being done. Community Living Sarnia Lambton has operated a summer employment program for people who have a disability for over 15 years and it has been growing exponentially in recent years. In the summer of 2011 they found paid summer jobs for 82 kids with disabilities. All types and degrees of disability, students from high school, colleges and universities, and all types of jobs – 95 jobs in total as some kids had more than one job.

There are many benefits and layers to the successes of this program. The agency accesses multiple funding opportunities through the provincial government and federal Opportunities Fund, along with corporate sponsorship and agency fund-raised dollars. In this way, public funding is leveraged to maximum benefit.

Another element is that the ‘job coaches’ are themselves University and college students, without disabilities, and hired through federal and provincial summer jobs programs. These future business leaders also learn about the benefits of including people who have a disability in the workplace.

The most telling aspect of the program, however, is the change in dynamics within the families of those with disabilities and educators. The agency notes that the greatest change is in families who suddenly gain a sense of hope and expectation as they realize their kids can work and will have a place in society. This change in expectation that work is the next logical step after school is significant. Young people with disabilities in Sarnia are now graduating from school and approaching the agency immediately for assistance to find work. No longer is social assistance the first step. For many, it has become the fallback, as it rightfully should.

At the end of the summer the students created a video to celebrate their success. It can be accessed at: http://tinyurl.com/2b56zh8

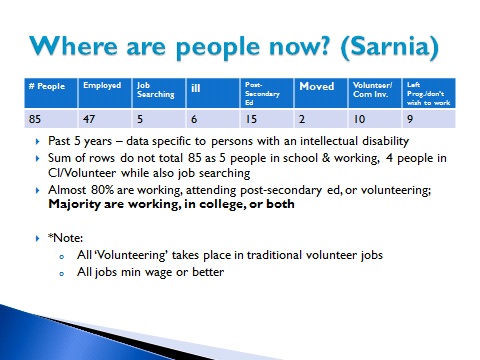

While Community Living Sarnia’s summer employment program supports people with all types of disabilities, the agency was asked by Ontario’s Ministry of Community and Social Services to track the movement of those in the program who had an intellectual disability. Those results are in the table below:

In summary, I would like to say that we need to invest in youth with disabilities; we must engage the private sector in a different way and ensure that we can support them to be successful; and, that we need to ensure efficient and seamless access to the services and supports people who have a disability need in order to be successful contributors to the Canadian economy.

For more information, contact:

Joe Dale, Executive Director

Ontario Disability Employment Network

905-706-4348

Sources:

*1 Carter, E.W., Austin, D. & Trainor, A. (2012). Predictors of Post school Employment Outcomes for Young Adults With Severe Disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23(1), 55-63.